On a humid July day, the barn at the first of Kate Stillman’s two farmsteads in Hardwick is filled with cheeping. Dozens, or perhaps hundreds, of young turkeys occupy one side of the nineteenth-century structure, their pink faces wearing the perplexed look that young turkeys always seem to have. Their short lives will end a few months later at a second farm in the southern part of town, where Kate has recently added a poultry abatoir that gives her greater control over the growing meat business she started ten years ago.

The presence of the turkeys links Stillman Quality Meats with the past of this particular farm at the corner of Thresher and Jackson Roads. But it also represents an interesting moment in the longer history of agriculture in central Massachusetts. As area farmers found it harder and harder to compete with large-scale industrial food production, especially after the Second World War, many owners of small farms like this one shifted from full-time to part-time or seasonal operations and sometimes to “hobby farming” that removed them from commercial markets altogether. But when farmland has been owned by people who have cared about keeping it as farmland, the properties have remained as potential resources for newer enterprises, like Kate’s, that are part of today’s attempt to rebuild more locally- or regionally-oriented food systems.

In the 1820s, what seems to have been a modest eighteenth-century farm came into the hands of the Cleveland family, who owned a good deal of property in this northern part of Hardwick. In 1869, they sold it—now augmented to a 160-acre parcel—to a recently-married young Irish couple, Michael and Ellen (Carney) Mahan.

The Mahans appear to have been highly skilled and energetic farmers. They accumulated the capital needed to buy and run a farm within ten years of emigrating to the U.S., and in their first year at Thresher Road, with minimal equipment and only a 12-year-old hired boy to help them, they produced not only the corn, wheat, and potatoes that were common cash crops at the time, but also an impressive 3,000 pounds of cheese, suggesting that Ellen, who at 30 had just delivered the couple’s first child, was, like many farm women, an adept cheesemaker.[1] They also sold meat and a good deal of wood. Ten years later, the 1880 census showed that their “unimproved” acres had been converted to income-producing pasture, orchard, or woodlot and that they now had three sons and a daughter.

The Mahans’ mixed farming operation was similar to countless others in central Massachusetts in this time period. As profits from meat and grain dwindled when railroads began bringing products from much larger farms to the west, people in Hardwick found new sources of income, not only from the textile and paper mills that were appearing by mid-century but by a significant level of both on- and off-farm cheesemaking. Three “cheese factories”—small-scale operations that bought milk from a number of nearby farms—were operating in Hardwick by the 1850s and accounted for more than half of the 300,000 pounds of cheese made annually in the town.[2]

But by the time Michael and Ellen Mahan set up their farm, cheesemaking, too, was feeling competitive pressures from western and midwestern states. We have no detailed data about what the Mahans produced in the later years of the nineteenth century, but if they continued to follow the general local pattern, they likely shifted more toward liquid milk dairying, perhaps with an increased emphasis on their orchards, poultry, and market gardening. [3]

Michael and Ellen died within a few years of each another in the first decade of the twentieth century, and their son Daniel and daughter Mary kept the farm going for several more decades. Mary died in 1932 and the 1940 federal census shows Daniel living there with a hired farmhand. When Daniel died the following year, the youngest Mahan son, John, then in his 60s, began coming back to Hardwick from his home in Springfield, where he had long been a traveling salesman in the food industry. John was the only one of his siblings ever to marry, and a 1920s family portrait of him with his family gives a clear sense of the middle-class aspirations of this one-time small-town farm boy. And yet he seems to have been unwilling to let the old family farm go.

John had an ally in his efforts to maintain some kind of farming activity: his son-in-law, George Crombie, who had married John’s oldest daughter Elizabeth. George was an Irish-American from Connecticut whose family owned an ice delivery business and also operated a fleet of school buses. Although George attended college and worked in the family companies, he himself seems, like Winfred Fellows in Warwick in the same time period, to have wanted nothing more than to be a farmer. As a boy, he belonged to 4H, raised hiefers, and won an award from the state for his agricultural accomplishments. And when his wife’s old family farm was in need of stewardship, he jumped immediately onto the bandwagon, lending a hand with haying and buying his father-in-law “a couple of turkeys to keep him busy,” in the words of George’s daughter Susan Twarog.

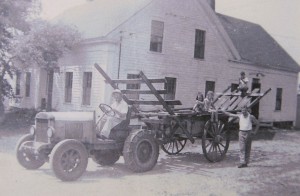

Before long, the “couple of turkeys” had expanded to a seasonal business in which the two men raised up to 5,000 free-range birds annually. They bought day-old chicks in Connecticut and kept them inside the barn until the Fourth of July, then put them outside with fencing and flares to keep the foxes away until the turkeys were big enough to protect themselves. After John Mahan died in 1956, George kept the business going himself, slaughtering the birds in the barn until about 1960 when more stringent regulations required him to build a separate government-inspected processing plant on the property.[4]

In his work for regional food wholesalers, John Mahan had actually been helping to widen the gap between small-scale producers and the increasing consolidation of food production and distribution. He and his son-in-law weren’t really able to compete in those expanding markets; George’s daughter Susan notes that her father was lucky if he was able to break even at the end of a year. But the two men—and a generation of young cousins who loved spending their summers at the farm—seem to have been motivated more by passion and place-attachment than by the profit motive. And they did find buyers for their birds: they sold turkeys to stores, restaurants, hotels, and hospitals, and did some direct-marketing to customers as well. It was laborious and rather old-fashioned, but it kept the farm functioning.

There has been only one gap in this farm’s operations: between 1975, when George and Elizabeth Crombie finally sold the property out of the family, and 1985, when it was bought by Bob and Linda Paquet. The Paquets were not commercial farmers, but they raised sheep for wool, restored and renovated the house and barn, and very much saw themselves as carrying on the Turkey Farm name and presence in the town. Their children belonged to 4H. And the family entered a three-tiered float in Hardwick’s 250th anniversary parade featuring a three-dimensional, living rendering of this old farm’s story. On the bottom layer, one of their daughters and a friend wore period costumes to evoke the Mahans’ dairy farm; George Crombie and his daughter Sue appeared with a live turkey on the second layer to represent the Turkey Farm years; and on top, the Paquets’ pet ram, Napoleon, was a literal link with the present moment on the farm.

With its current owner, who bought it from the Paquets in 2005, that story takes another turn. Kate Stillman’s grandfather was a dairy farmer in Lunenberg, Massachusetts, and her father Glenn started there to build an extensive direct-marketing business that now encompasses farmland in Lunenberg and Hardwick’s neighbor New Braintree.

The Stillmans coordinate their efforts and their collective presence in markets around eastern and central Massachusetts. Kate’s brother owns a farm just north of Hardwick Center, and Kate purchased a second Hardwick farmstead seven years ago, where she built her abatoir. Together, the family is able to offer a much wider and year-round range of products than most small direct-marketing operations. They are somewhere in between very small and large scales, serving customers who value a sense of face to face interaction but who also expect consistency and variety.

“It’s a hard stretch,” Kate admits. “If you have people who are used to going to the grocery and fancy high-end chain stores, they just are used to seeing that produce there. And they don’t understand that the peaches might not quite be be ripe, you know, that the turkey didn’t grow to 27.2 pounds, it only grew to 26 pounds! So being able to do our own processing actually has helped us narrow that gap a little bit and get closer to what people’s expectations are.”

Kate always intended to put her own name on her business. But local memory was strong enough that she found she couldn’t quite shed the Turkey Farm name, and the new farm started out as “Stillman’s at the Turkey Farm.” More recently it has been renamed Stillman Quality Meats, but the turkeys Kate felt obliged to add to her repertoire still fill the barn on Thresher Road each summer and fall. And Kate herself seems to have a sense of where her business fits within these complex, overlapping trajectories.

“I couldn’t imagine trying to do this in a different time period,” she says. “It’s nice being in an area that’s so booming and blossoming and nice to have the support.”

Click here for a gallery of additional photos from the Turkey Farm and Stillman Quality Meats.

[1] On the gendered nature of mid-nineteenth-century dairying in New England, as well as the emergence of “cheese factories” around the region in the same time period, see Heather Paxson, The Life of Cheese: Crafting Food and Value in America (University of California Press, 2013), pp. 99-102.

[2] Massachusetts Historical Commission, Reconnaissance Survey Report for the Town of Hardwick (1984), p. 8.

[3] Reconnaissance Survey Report, pp. 11-13.

[4] In an interview with the industry magazine Turkey World in January 1962 (pp. 97-98), George Crombie noted that he was “well pleased” with the new facility. “My plant is rather cramped for space, but sufficient.”