There were five local slaughterhouses in Athol when Beverly and Lewis Adams began to sell packaged meat as part of a transition away from the increasingly unprofitable business of dairying. Lewis slaughtered the cows and pigs they raised on their Bearsden Road farm, an Italian butcher from Donelan’s market in Orange did the cutting, and Beverly packaged the meat for her husband to sell around town. The business grew, and after Lewis died suddenly in 1973, Beverly kept it going as a way to support her five children.

She was also continuing a trust from her mother-in-law, Hester (Comerford) Adams. Hester was born in Athol in 1885 and grew up on a farm a little farther along Bearsden Road from the spectacular spot at the crest of the hill occupied by the present-day Adams Farm. Hester’s father, Richard Comerford, was the son of Irish immigrants who became a veterinarian in an era when horses provided much of the point-to-point transportation in both urban and rural places. Injured city horses were often sent to the country for rehabilitation, and Richard seems to have been among the several animal doctors in Athol—his son became another—who attended to them.

But the Comerford women were equally involved with both doctoring and animals, a facet of this farm family that continues into the present day. Hester was the youngest of nine children; her oldest sister Ethel pursued a medical degree in the early twentieth century, interning at the Massachusetts Homeopathic Hospital and later running her own practice in Leominster and the North Shore. (Homeopathy, now an “alternative” medical practice, was much more mainstream at the time, and many women were homeopathic MDs.)

And Nora, two years older than Hester, became a farmer in her own right, working with her brother Tom to keep the Comerford dairy farm going through the challenging 1920s and 30s. Like many other area farm families, they both sold to people in the industrial towns and sometimes worked there themselves—in Tom’s case, in one of the local tool factories. Nora was the farm’s mainstay: Athol street directories and federal census records list her variously as a milk dealer, a farmer, and a “farmerette” (a term used during World War I for young women who took over farmhand jobs usually held by men who were away at war).

In 1915, at the age of 30, Hester married a man from a French Canadian family, Lewis (Louis) Adams. Hester, not her husband, seems to have remained the primary farmer and land-owner; four years after her marriage, she purchased some land next to her family’s farm and used it to pasture and milk her own dairy cows. The couple had three sons—Hector, Charles (Chuck), and Lewis Jr—but the marriage did not last. By the end of the Depression, and continuing into the 1950s, it was Hester and her two oldest sons who were working the farm. The sons also inherited the neighboring Comerford farm when Nora died of breast cancer in the 1940s.

It was Hester’s youngest son, Lewis, who built the first slaughterhouse at the top of Bearsden Road. That was in 1946, at a time when it was already becoming more of a challenge to keep small-scale dairying profitable. When Lewis married Beverly Heath in 1955, it was becoming clearer that they would have to adapt and change if their business was going to survive. Beverly has a very clear recollection of her new mother-in-law entreating her to keep the farm in the family. It was a charge that struck more deeply when Hester died of a sudden heart attack that year at the age of 70.

Lewis and Beverly worked together to reinvent their hilltop operation. Lewis had always raised some heifers for meat, but they expanded this sideline, added pigs, and began growing corn to feed the animals. They built a new slaughterhouse in the late 1950s and stopped dairying altogether. They found customers among both farmers needing slaughtering services and—once they added a small retail store—shoppers looking for good affordable meat. In the 1960s they sold the old Comerford farm to reduce their tax burden, concentrating on raising their family and expanding their new specialized trade.

In the early 1970s, they had just updated the slaughterhouse again, building a larger facility on the eastern side of Bearsden Road, when Lewis died suddenly, leaving Beverly with five children under 17 and a challenging business to run. She kept it going, eventually taking her children into partnership with her, and Adams Farm remains in family hands, with some of Beverly’s grandchildren now involved as well. Beverly still comes to work most days, although her daughter Noreen and son Rick now run most of the day-to-day operations.

They do so in a greatly-enlarged facility, one that was completely rebuilt after a devastating fire shortly before Christmas in 2006 burned the 1970s structure to the ground. The resurgence of Adams Farm is a source of pride for many people in a town that still struggles to define itself after the loss of much of its major manufacturing in recent decades. In fact, the slaughterhouse is now the largest in New England and a vitally important node in the “local food” economy not just for Athol and the North Quabbin, but for the entire region. More than 500 small farms avail themselves of its services, and its retail store is almost a mini-supermarket in its own right, albeit one with a very heavy emphasis on meat.

Many of the farms that send their animals here go to great pains to emphasize the beauty of their own pastoral settings, the health and individuality of their livestock, and the aesthetic pleasures of the meat they sell. Adams does none of this: it is a resolutely utilitarian business, homey and practical in an unpretentious way.

It is, in fact, a somewhat paradoxical place, local and not local, agricultural and industrial, a functional complex in a stunningly beautiful location. It is crucial to today’s rapidly-expanding (and often upscale) food movement in New England, but it is itself firmly rooted in an older agricultural economy and closely tied to the blue-collar identity of the area. Few of its own retail products are local; much of the beef in the store comes from Amish farms in Pennsylvania, while most of the pork is from Canada. (Rick Adams makes long trips each week in the Adams Farm truck to pick it up). But all of it is humanely raised, hormone and antibiotic free, and processed on-site, placing Adams Farm somewhere between old and new, organic and conventional, artisanal and industrial.

It might seem that the four-generation legacy of women being centrally involved in running this farm and slaughtering operation is somewhat paradoxical as well. But the women themselves don’t see it that way. For Beverly (now Mundell), the business is what was in front of her when she needed to provide for her family. For her daughter Noreen Heath-Paniagua and Noreen’s daughter Chelsea Frost, this is simply what they’ve known all their lives—“It’s all I know,” in Noreen’s words.

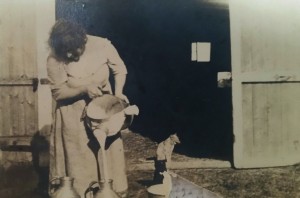

They do admit to finding inspiration in a photo of Nora and Hester Comerford standing next to each other looking as though they’ve just finished milking. The photo hangs in several places around the building, one of only a few family photos that survived the 2006 fire. “They’re like my heroes, just seeing how hard they work,” Noreen says. “That’s the motivation that some of us need to keep going sometimes.”

Beautiful, brings back sooo many beautiful memories,I remember Hester,an I believe she is the one on the right,I was blessed too watch it all happen,such a hard working family.We sure could use some of that today!! Love yall an God bless what the future may bring We love yall!!

Tony an DeeDee Allen,!!!